One doesn’t earn the nickname “Black Death” by navigating lethal situations with kindness and words. What follows is the story of African American soldier Henry Johnson, a legend of the First World War.

The Early Life of Henry Johnson

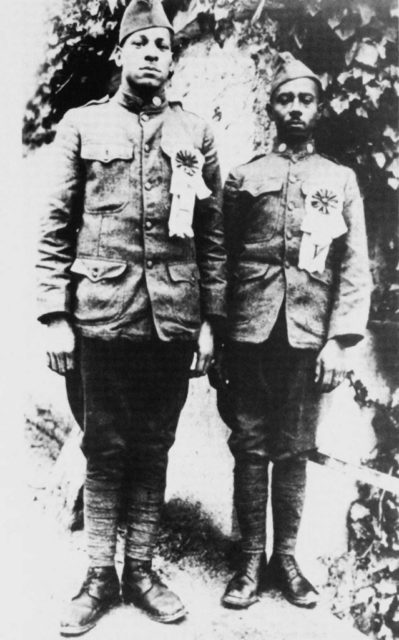

William Henry Johnson was born in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, in July 1892. As a teenager, he moved to Albany, New York, and worked a number of jobs. According to an article on the US Army’s website, he was a chauffeur, coal-yard labourer, and a train station porter, among other things. We know little else about Johnson’s early life, though. On the 5th of June 1917, he signed up for a black national guard unit commanded by white officers. The unit operated out of Harlem and was later redesignated the 369th Infantry Regiment. But you might know it by its other name: the Harlem Hellfighters.

Henry Johnson in the Great War

With World War I still raging, the US Army sent the Hellfighters to France. The voyage there was nightmarish, taking about three months in all. In a snowstorm, another ship rammed the Hellfighters’ ship. The exhausted men had to repair the vessel themselves. They arrived on New Years Day in 1918. The thing is, the Hellfighters didn’t even fight alongside American units. With the racial tension of the time, the higher-ups attached the Hellfighters to the French 161st Division. The 161st was a colonial unit, and they were right to welcome the Hellfighters. Shipped to France unarmed, it was the French Army’s responsibility to weaponise the Hellfighters. By at least the 14th of May, they were defending an outpost in the Forest of Argonne in France’s Champagne region. This was where Johnson earned his infamous nickname.

Henry Johnson vs the German Army

On the night of the 14th, Johnson was on sentry duty in a forward observation post. At his side was one Private Needham Roberts. If things hit the fan, they would be virtually on their own. In the dark hours of the morning of the 15th, Johnson sighted movement in the trees. He roused Roberts from his slumber. Not a moment later, at least a dozen soldiers of the Imperial German Army were in Johnson and Roberts’ midst.

Despite being outnumbered, the Americans chose to fight. Johnson sustained a number of wounds in the hour-long firefight. At one point, the Germans took hold of a badly wounded Roberts. Likely they would try to extract vital information from him. But Johnson wasn’t having a bar of it. He dashed into the midst of the enemy with a Bolo knife and buried it in a soldier’s head. Alone, he then defended Roberts with his knife, the butt of his rifle, and his bare fists. He slew four and wounded others, and the survivors soon realised they were outmatched. They tucked their tails between their legs and ran. Throughout the engagement, Johnson sustained 21 wounds, including bullet and bayonet wounds. He also managed to save Private Roberts. As a side note, some of the more generous estimates put as many as 32 Germans at the site of the carnage (instead of 12).

For his bravery, the French awarded Johnson the French Croix de Guerre avec Palme. This was the nation’s highest award for valour. The US Army, on the other hand, gave him nothing.

Remembering Henry Johnson

When Johnson returned to the States, he received some media attention and took on some paid lecturing work. In his lectures, he was supposed to speak about racial harmony in World War I. One night, he couldn’t stomach the lies anymore and told the truth. The army responded by trying to arrest him for wearing his military uniform after the end of his commission. His lecturing came to an end, and his war injuries made many other jobs impossible for him. In 1929, at 32 years of age, Johnson succumbed to a heart condition called myocarditis. He died poor, young, and forgotten.

A full 78 years after that bloody night in France, the US military finally pulled its finger out and started giving Johnson the recognition he deserved. President Bill Clinton awarded him a posthumous Purple Heart in 1996, and in 2003, the Distinguished Serviced Cross followed. In May 2015, President Barack Obama awarded Johnson the Medal of Honor. At the presentation, Obama said the following:

“We have work to do as a nation to make sure that all of our heroes’ stories are told. The least we can do is to say, ‘We know who you are, we know what you did for us. We are forever grateful.'”